Fish and Parasites

Long before I was into complementary health matters and a Hulda Clark fan, I knew a little about parasites. I realized how frequently fish harbor worms (often still alive long after the fish is dead). When I started looking for them, I became so disgusted that the only fish I would eat for a year were shrimp (the parasites are too small to see) and sushi.

Sushi restaraunts typically use the cuts and species least likely to harbor worms (mostly coldwater fish). If there is a worm or eggs, the chef is trained to spot and remove them (watch one carefully sometime). Warmwater fish that typically harbor parasites, like mackerel, shrimp, and eel, are usually served pickled, smoked, boiled, or otherwise cooked even in a sushi restaraunt. Add to that the horseradish (colored green to look like wasabi) which is antiparasitic and antibacterial (as is the ginger and miso), and it seemed to me a good route to prevent worms. However, after a few stories of people becoming acutely or chronically ill from eating at sushi restaraunts, I stopped eating at them as often.

When I was young, I heard a story about someone at a chain fish and chips restaraunt finding live worms wiggling inside a filet into which he had bitten. I did not really believe it even then, and as I became older and starting mentally cataloguing what I then called "modern American folktales" (a decade later to be known as urban legends), I thought back on that tale and put it into the same category as the poodle in the microwave. Now, I'm not so sure. The Journal of the AMA reported a case in 1988 where a woman noticed worms crawling around inside a piece of haddock she had cooked in her microwave. They were anisakids (see below). Haddock is commonly used in fish and chips restaraunts.

After a year or so, I got over my revulsion to cooked fish and began merely ensuring the fish was cooked at least medium-well (a real pity since it destroys the taste), and just did not look closely at the worms. After all, they are a source of protein (grin).

A few people to whom I related the worms-in-fish stories became even more revulsed than myself, and a couple did not eat fish for years. One of them, wondering about the validity at first, asked the fish monger at a market if it was true. "Sure," he said, "lots of them. Worst in amberjack. Sometimes I have to throw the whole tail and head sections away." The monger said he thought tuna and farm-raised catfish were the least wormy.

One of my brothers fishes a lot. He first clued me in by pointing out the worms while he was fileting large saltwater fish. I like to eat fish he filets since he fastidiously removes them. He has noticed, like me, that coldwater fish tend to have less worms than warmwater ones. Sea trout are typically very wormy and not worth keeping. Grouper was once considered a trash fish due to the number of worms it contained and cost about the same as cheap catfish, but people obviously do not notice them as much any more since they are now one of the more expensive.

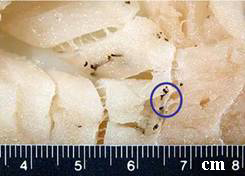

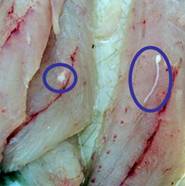

According to him, fish that flakes the most when cooked usually has less worms (except amberjack), and they are easiest to remove when they are present after cooking. Worms appear like thin white strings which pass through one or more flakes. The muscles (flakes in fish) are connected by ligaments which also look like white strings, but these are attached between the flakes with a spider-web-like structure and break near the middle when the flakes are separated. Worms will thread through the flakes and if the flakes are pulled apart carefully the worm will pass through and be attached to the next flake.

The fish which seem to contain the most worms are, in my observation and my brother's, are amberjack, sea trout, mackerel, catfish (even farm raised - the fish monger had obviously not fileted or eaten too many of them), "orange roughy", and other fleshy fish like catfish which does not flake easily.

When there are worms in the fish, it is also likely there are eggs, too. They might withstand heat better than mature worms so be more likely to be ingested while still viable.

A typical fish parasite is the fish tapeworm. It is thought to be the longest worm which infects humans at over 25 ft in length, and can live many years in the intestines, often without causing many problems besides B-12 deficiency, possibly causing anemia and/or fatigue. Anne Gittleman, in "Guess What Came To Dinner," says that the most common fish to be infected with tapeworm are salmon, pike, perch, lake trout, grayling, orange roughy, and turbot. She mentions other fish parasites, like anisakid worms, can cause appendicitis as well as Crohn's and other intestinal ailments. They must sometimes be removed by surgery if they are embedded in the intestines.

Gittelman discusses a 1988 German TV program which ran a story where they investigated herring and found worm larvae in the bellies and flesh, as well as live ones in jars of pickled herring in the supermarket (maybe even pickled sushi isn't so safe). As a result of this program, the "entire nation revolted when they learned of the infestation of worms in native fish. The West German fish market virtually collapsed overnight."

I think these and other worms carried by popular food fish cause less parasitic illnesses in the US (the great majority of which I think are un- or mis-diagnosed) compared to other species of parasitic worms.

People who have healthy digestion, with plenty of acid, enzymes, and throughput, have little to fear from parasites as long as they are reasonably hygeinic. Ingested eggs and perhaps worms will be destroyed or flushed away before they can become established. To minimize risks from parasites in fish, ensure it is cooked thoroughly. Cabbage, onions, and vinegar are antiparasitic. Eating cole slaw with cooked fish is prudent.

From Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Imagine a day fishing out on the water and everything seemed great. A legal limit of good-sized fish has been caught, plenty for a tasty dinner upon returning home. But while filleting one of the fish, there are spots found in the muscle, or even visible worms. What is one to do, cut out those areas and continue to cook and enjoy the fish for dinner, or throw it away? Although these parasites may not look very appetizing, worms are commonly found in marine fish and are rarely passed from fish to humans. It is safe to cut away the affected area and continue to cook the fish as usual. Even if parasites are present cooking kills them and they are not a risk to public health.

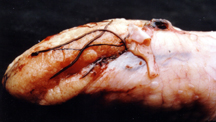

Parasites are organisms that live on or within another organism, called the “host.” Most fish species are susceptible to worm infestations but a few species, particularly those in sharks and fishes in the grouper, amberjack, and drum families, appear to be more susceptible to them. Larger, older fish can acquire many parasites over the course of their lives. Though they appear to be very intrusive, parasites rarely cause health complications for the fish. Although most commonly seen by anglers in the muscle, parasitic worms can live in every organ. For example the ovary of this grouper is inhabited by large, red nematodes or “roundworms.” In general, parasite density and diversity can be good indicators of the overall health of a marine environment. Fish possessing a high diversity of species of parasites in relatively low abundances are commonly found in healthy marine systems. |

Links California Sushi Academy - Learn how to really clean fish. |